2331 St. Claude Ave and Spain, New Orleans, LA 70117 504- 710-4506 Tues-Sat 11am-5pm Andy Antippas, Director Directions

UPCOMING

PAST EXHIBITIONS

FEATURED ARTISTS

HISTORY OF BARRISTER'S

ST. CLAUDE COLLECTIVE

AN EXHIBIT FOR PROSPECT.1

THINGS OF INTEREST

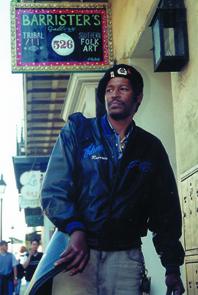

HERBERT SINGLETON

ROY FERDINAND

AFRICAN

HAITIAN

THE METAL ART OF HAITI

(catalog essay)

ANTIQUITY UNVEILED

2331 St. Claude Ave & Spain

New Orleans, LA 70117 504-710-4506

Tues-Sat 11am-5pm

Directions

Contact

Go to Galleries Map

for more galleries

on St Claude Ave.

1959 - 2004

View Roy's work

All of which should situate his

work within the grand social realist tradition of Courbet and the

legions who followed in his wake, but Ferdinand departs from that

tradition in certain works that seem to almost celebrate the depravity.

Not in the naively pumped-up way that gangsta rap celebrates

sub-moronic mayhem, but with unexpected twists of his own. For

instance, Freek Show depicts a couple of gangsta dudes on a

sofa enjoying the spectacle of a foxy babe, naked on the floor, being

intimate with a young Rottweiler. Fortified by her crack pipe, she

seems unperturbed by her situation or by how she appears to her

appreciatively snickering companions. Beyond the obvious twists of the

scene itself, Ferdinand throws another curve ball by making these

figures appear not entirely unsympathetic. The dudes on the sofa seem

more impish than evil, and the girl displays a stoicism that almost

approaches something like dignity in spite of it all. (It is, as

Ferdinand might say, a mindf--er.) Related more in content than in

tone, For the Sake of Rock is another twisted scene in which a

young boy sleeps on a mattress on the floor as roaches and rats swarm

all around him. Just through an open door, crack pipes and sexual

favors hold sway, and in this instance, at least, there is no

ambiguity; Rock is a cautionary depiction of societal ills in

the grand social realist tradition. Equally unambiguous is Esplanade

Unsolved, a view of a naked female corpse in a noose hanging from a

tree. Blood issues from a variety of wounds in her battered body, as

one half-open eye gazes back at us. It could be anyone, but gang

graffiti on the wall suggests that this is yet another victim of a

deadly demimonde, another lost soul from a crack-house hell realm.

But death and depravity are

equal opportunity employers, and there is no dearth of male victims and

female potential victimizers here. What can be disturbing is

Ferdinand's tendency to glamorize the deadly femmes in question, while

equating women with types of guns in images such as First Ms. 380,

in which a foxy brown sugar babe lies on her bed in bikini briefs and

not much else, as she fondles her pistol. The girl is glamorous and the

scene suggests a Gert Town version of Miami Vice, but what

does it mean? Is it glamorizing bad stuff, or is Ferdinand empowering

women by making them formidable? Much of this can be disturbing, but

the ambiguity encourages viewers to think for themselves. The work is

powerful and sad, and Ferdinand sometimes seems to be stuck there --

but then, so are we, as long as such conditions exist. Strong stuff.

More twists appear in The

Devil and the Bird of Love in the adjacent gallery, a group show

about love and the diabolical chaos that it sometimes causes. Heavy on

collage and mixed media, it also has its share of mixed messages and

mixed results, but it's a nice, light counterpoint to the nearby

heaviness. Among the more polished pieces are curator Raegan Robinson's

Jewelry Box, a delicately ironic artist's book that

functions as a rumination on love's stages. And Jane Batty's cigar box

allegories of romance, movie stars, tropical birds and other flighty

things are especially eye-catching. The collages and constructions of

Mat James and Nicole Geraci are as solidly and intriguingly gothic as

always, and Heather Weathers' Furry Dick lives up to its name.

But Patti D'Amico's paper retablas (actually iconic paintings based on

Mexican lottery tickets) are surprising, elegantly illustrated

explorations of the pop-psyche ramifications of El Diablo's

machinations. Colorful, illuminating and just the thing for Lent.